Dear Friends and Colleagues,

In these unprecedented times, due to widespread censorship heretofore seen only in totalitarian countries, but now occurring in our own, one of the biggest challenges we face is our ability to discern the truth.

The consequences of being unable or unwilling to discern have never been more pressing, calling to mind an ancient yet timely warning…

‘Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness…’ (Isaiah 5:20)

In general, people can’t be rushed to accept a painful truth unless they’re ready. Regardless of how much credible evidence is presented, if someone is in denial due to psychological or spiritual obstacles, no amount of proof will convince them otherwise, especially if the evidence threatens long-held beliefs that are fundamental to their identity.

Pride and ego may also play a part in denial. If someone considers herself educated, it can be hard to admit she was wrong about something important—that she was duped by others. I recently heard a woman lament that she felt like a “useful idiot” for having unwittingly supported a politician she later learned was corrupt.

It’s also conceivable someone may resist admitting he was wrong because he fears it would make him look weak, thereby diminishing him in the eyes of those who look up to him, but it bears remembering that there’s no shame in having been deceived by charlatans. The shame belongs to the deceiver, although that’s an unlikely response for those who habitually deceive.

In fact, it’s a sign of strength when someone is able to admit he was fooled, or can own a big mistake. Employees admire when their boss can take responsibility for an error. Children whose parents are willing to show fallibility are able to model how to be human themselves. Saying, “I was wrong. I’m sorry” is liberating for both parties and a sign of psychological maturity.

At the end of the day, each of us has a unique path to navigate that can’t be charted by another. We don’t know what emotional or spiritual battles others are facing which may prevent their discernment.

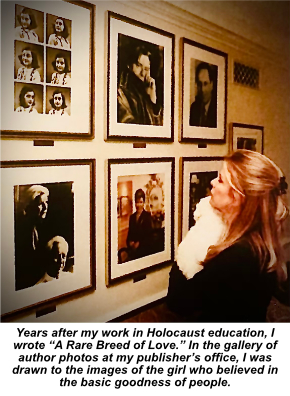

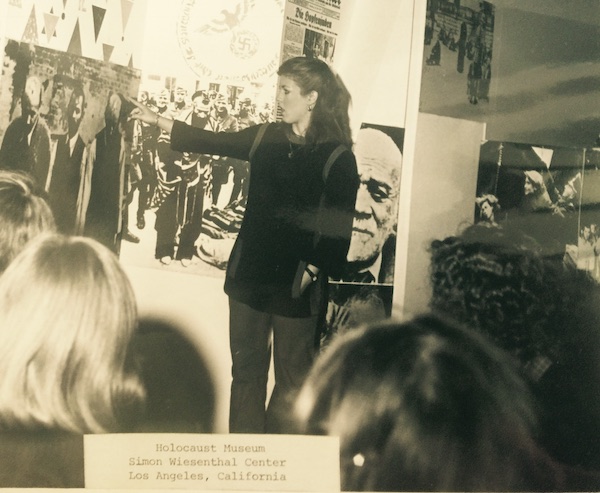

My own journey during this surreal period is reflected in various art and writing projects, as well as new professional activities. This updated website includes some of those endeavors.